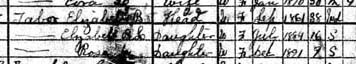

As Women’s History Month winds down, census records are on my mind. They are a blessing and a curse to the biographer. Once again, I am researching a Victorian Colorado woman who was fashionably demure about revealing her age and birthdate. Elizabeth “Baby Doe” Tabor was born in 1854. I am not sure of the exact date, because I have encountered negative evidence in that regard. She attained the age of six by the 1860 census. If my math is correct, she would have been 46 years old in 1900. The newly widowed Baby Doe figured it out differently. In 1900, her birthdate is shown as 1861 and her age as 38, thus not breaking the dreaded 40 barrier.

Baby Doe was not unusual. Literally every woman I have researched during the Victorian Age lied about her age and birth year on census records. The age is never higher. Male pioneers rarely deviate from their birthdate. What does all this mean? Perhaps women back then felt a need to work harder to maintain a youthful demeanor and appearance for a variety of reasons. It could strictly be a case of feminine vanity. As a result, I work harder to prove my facts, and I usually discover more insights along the way. So it goes.

This subject was on my mind recently as I filled in my 2010 census form. Thinking ahead, would my children’s children some day find some interesting data as a result of my entry? In spite of their flaws, or possibly because of them, census records reveal interesting facts and perceptions about those who precede us.

Joyce B. Lohse, 3/28/10

www.lohseworks.com